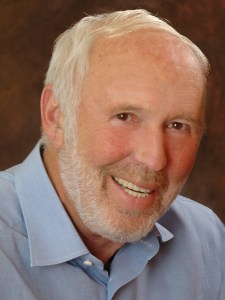

“I remember you,” said James Simons, origin of life philanthropist, math genius, 60s peacenik and so much more, searching my face with some intensity as he greeted me in September 2014 at his New York office in the Simons Foundation, which he chaired.

Indeed, we had met months earlier at a public lecture on von Neumann machines that the Simons Foundation hosted downstairs in its state-of-the-art theater. Simons at the time invited me to stop by for a tour and interview for my book on origin of life—with the caveat that he knew nothing about origin of life.

Simons then spent much of the summer aboard his yacht Archimedes, sailing as far as South Korea to address the International Congress of Mathematicians in August. Our interview was scheduled for his return from the Far East, and I was delighted when he decided to share his perspective with me on origin of life.

It was a Friday afternoon, the day after Jewish New Year when we met again. The office was empty except for Jim Simons’ closest assistants. I was struck by the composure of the setting. White shades transformed the view from the foundation’s windows overlooking the Flatiron district, and there were none of the usual distractions: No photos of Simons shaking hands with world leaders, cigar-smoking generals or revolutionaries. No sports trophies. Not a single ancient artifact in sight.

The centerpiece of the foundation’s executive suite of rooms seemed to be a series of canvases along the wall leading to the chairman’s office, painted in vibrant fuchsias, yellows, blues, greens.

But it’s his Chern-Simons equations that have significantly influenced today’s thinking in physics that Simons framed inside his office.

Forbes magazine at the time listed Jim Simons as the 93rd richest human with an estimated wealth of $12.5B. The hedge fund he chaired, Renaissance Technologies—which enabled his philanthropy —then had roughly $23B in funds under management.

Understandably, Simons didn’t look for a lot of publicity. He seemed to have nothing to prove, was at peace with himself. He’d handled the tragedies in his life—notably, the loss of his two sons—by reaching out to help others through his philanthropy.

Jim Simons was mesmerizing in conversation. His eyes especially deep, but warm. Simons took you from the fury of life into his calmer world where he played with ideas until they had flesh and then delivered them with the irresistible bounce of Bogart.

Like other great minds, he was great fun, as evidenced by the what-it’s-like-to-be-a-billionaire interview he gave to a Black entertainment internet television show. It was staged with Simons sitting in a middle school classroom. “I’m Jim Simons, this is Celebrity High,” he said, sporting a gold Rolex and two gold rings (one his wedding band) and revealing that one of his top three favorite things about being a billionaire was being able to afford dinner.

Simons also enjoyed asking questions and trading stories. So we traded stories during the interview. I recounted the US bicentennial fashion show I modeled in at the Royal Tehran Hilton in 1976 when former CIA Director Richard Helms attended the gala in his official capacity as then-US Ambassador to the Shah’s Iran. Simons laughed when I told him we followed Spiro Agnew. (Agnew had resigned three years earlier in disgrace as Richard Nixon’s VP.)

Jim Simons was a native of Brookline, Massachusetts, the only child of a factory owner, and he still had a trace of a Boston accent even though a resident of New York for decades.

He began his career at age 14 working in the basement stock room of a garden supply store. Simons said he was soon demoted to floor sweeper, a job he liked because he could think about math, and about girls.

Along the way he married two substantial women. Marilyn Hawrys Simons, his widow, holds a PhD in economics from SUNY, Stony Brook and is considered an architect of the Simons Foundation.

His first wife, Barbara Simons, is an award-winning computer scientist with a PhD from the University of California, Berkeley.

Jim Simons received his undergraduate degree in math from MIT and then moved on, on scholarship, to study math at Berkeley, where he was awarded a PhD at age 23 — for his dissertation: On the Transitivity of Holonomy Systems.

By the 1980s, Simons was amassing a fortune trading foreign currencies while building the math department at Stony Brook, which he also chaired.

Jim Simons taught at MIT, Harvard, Stony Brook, and at Princeton. In the 1960s while at Princeton, Simons was also a cryptanalyst at IDA (Institute for Defense Analyses). It was at the time of the Vietnam War; he did advanced code breaking for the National Security Agency. Everything was “hush hush,” Simons said.

He told the South Korean Math Congress in 2014 the story about how he decided not to stay in the shadows about his feelings on Vietnam. Simons said the head of IDA, General Maxwell Taylor, fired him after he advised Taylor he’d given an interview to Newsweek in opposition to the war and written a letter to the New York Times as well saying war was stupid, a letter the Times published following its magazine cover story in which Taylor said the US would soon win the Vietnam War.

Jim Simons attributed his success in life not only to his understanding math, but to the extraordinary people he decided to partner with, plus good luck. He thought it was important to do something beautiful and original and not give up.

Indeed, Jim and Marilyn Simons’ generosity has been beautiful; they both signed the Giving Pledge to give away most of their wealth.

Jim Simons liked to sit front and center at Simons Foundation’s science lectures, which traditionally followed high tea. And he’d always have at least one profound question for the guest speaker. The foundation has continued its lectures following Jim Simons’ death in May. But his absence is palpable. . .