“These high frontiers are surely exciting, but whether it’s economical to go there to support the Earth’s population, I’m not sure. I think it more immediately feasible to concentrate on the planet we are stuck with and on. But it’s very important that we don’t overlook space, which is such a turn-on to such increasing numbers of people. Space exploration has got to be encouraged. Who can imagine what the horizons are? They’re limitless in terms of what we may learn about life.”—Malcolm S. Forbes in conversation with me in his office at Forbes, Inc., 1980

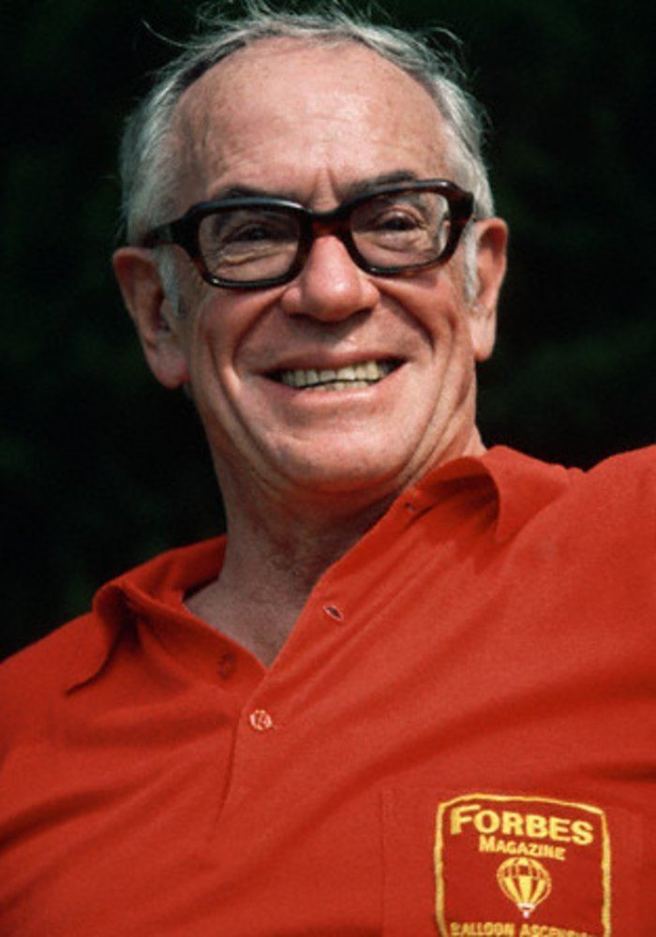

I first met Malcolm Forbes in the late 1970s with his motorcycle gang at Le Jules Verne, a tiny French restaurant in Manhattan’s West Village that the upper crusty families of New York used to frequent, and some time later called him at Forbes, Inc. where he was chairman, CEO, and editor-in-chief of Forbes magazine to request an interview. It was way before the Internet and before his appearance on 60 Minutes, at a time when Malcolm was being covered by Women’s Wear Daily and the motorcycle press for his various adventures as “the happiest millionaire,” beside penning opinions of his own for Forbes.

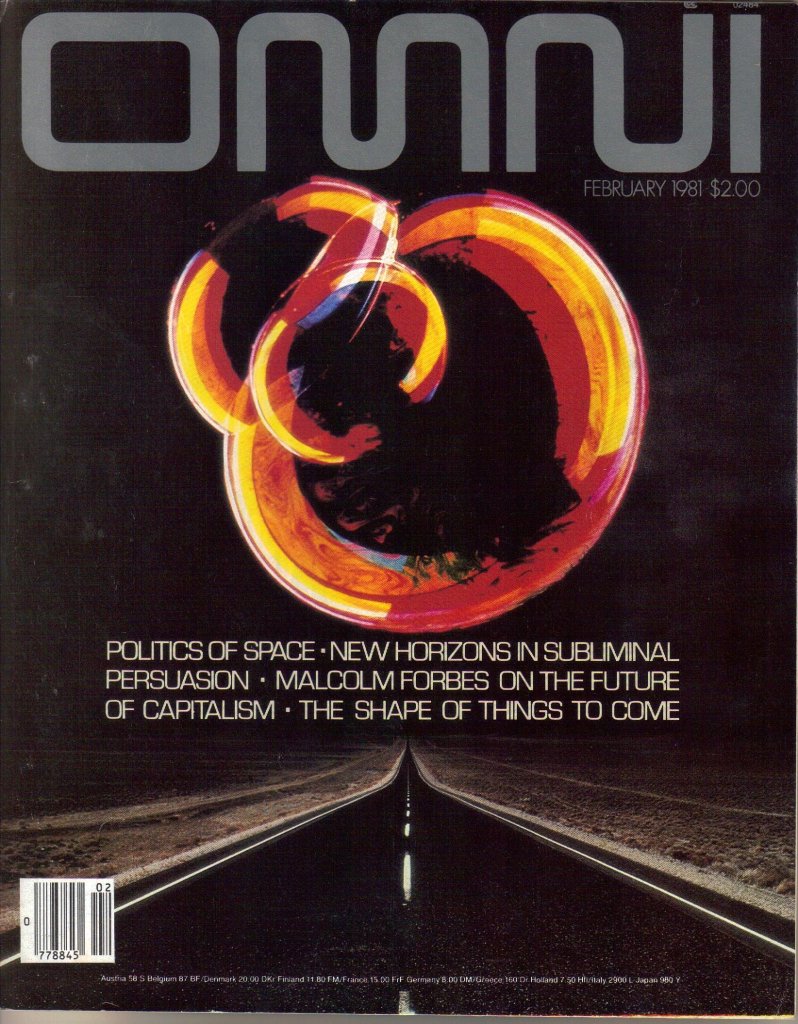

I’m republishing excerpts of my interview with Malcolm from that time because the discussion is still somewhat relevant and his humor ageless. The conversation first appeared in the February 1981 issue of Omni magazine with the cover blurb: “Malcolm Forbes on the Future of Capitalism.”

Malcolm several months later featured the interview in Forbes with the following banner:

“Editor-in-chief Malcolm Forbes was interviewed recently by author-journalist Suzan Mazur. Their discussion, published in Omni magazine, ranged from presidential politics and national defense policy to the allocation of mineral rights on Jupiter. (The latter, Forbes says, is not our most pressing problem today.)”

Excerpts of the interview follow (related story—Revisiting Futurist Malcolm Forbes on Science, Technology & Capitalism):

Since every last mineral can be found in space fiftyfold, do you think a principal aim should be to recapture the vision of space exploration that we quickly abandoned after we landed on the moon?

Forbes: Space is, pardon the pun, so far out that I find it hard to reach out and understand. I can understand mining the bottom of the seas, for instance, for these great nodules of valuable metals. The resources on this planet seem reasonably boundless. Space is so vast that it reaches beyond my comprehension.

Forbes: Space is, pardon the pun, so far out that I find it hard to reach out and understand. I can understand mining the bottom of the seas, for instance, for these great nodules of valuable metals. The resources on this planet seem reasonably boundless. Space is so vast that it reaches beyond my comprehension.

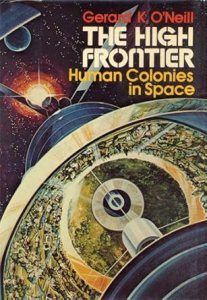

Are you familiar with the mass driver and with Gerard O’Neill’s book The High Frontier?

Forbes: These high frontiers are surely exciting, but whether it’s economical to go there to support the Earth’s population, I’m not sure. I think it more immediately feasible to concentrate on the planet we are stuck with and on. But it’s very important that we don’t overlook space, which is such a turn-on to such increasing numbers of people. Space exploration has got to be encouraged. Who can imagine what the horizons are? They’re limitless in terms of what we may learn about life.

As to giving exploration an economic basis now, though, it’s hard to see how the answers could lie out in space. At the same time, if we’re not out there exploring, learning—we’ve already discussed how corporations don’t anticipate the future—it’s a mistake. Considering all the products that have been derived from our space effort, we’d better hoist up our boot straps and get back into the act.

How do you view the Moon Treaty? Should the profits of space be shared equally among all the nations of the world, so that Sri Lanka, for instance, gets material benefits the same as France, even though Sri Lanka has no space program? Could private enterprise and Third World interests both be met in space?

Forbes: I think it’s a nice academic theory but the point is, who’s going to spend all the money to dig out the ore if all of it has to be turned over to the commune of nations?

You obviously can’t go out and stick a flag down, as in the old colonial days, and say the moon is yours. This is your Saturn. But you just can’t remove incentive and say everything belongs to everybody. That would mean nothing belongs to anybody, and nobody then would go get it.

Knowledge brought back from space, I feel, should be universally shared so that Uganda receives 100% of whatever we know. And Sri Lanka would also get 100%. But as for the material things, I think it’s a bridge that may not have to be crossed for a few lifetimes.

But what if we were to cross the bridge?

Forbes: It’s like Arabian oil. The Arabs were poverty-ridden nomadic people, in many respects, until they found oil. Presumably, they’re very pro-Third World. But as for how much they’d be willing to share with Sri Lanka, as far as I know, Sri Lanka is paying what we’re paying for a barrel of oil these days.

I think that if the French find a lot of ore on a particular asteroid, then France should be able to sell the ore in the world marketplace. Then somebody else will go after another asteroid for ore as entrepreneurs have done on Earth for oil and for everything else. Competition makes people go seek it and mankind profits universally. Though a drug company may own the rights to a certain medicine, mankind globally eradicates a certain disease.

It is the kind of academic question for which it would be wonderful to have a practical case to argue. I think we’ll all benefit when somebody does come back with something that everybody wants. We’ll all be the beneficiaries then, whether we have universally agreed to share equally or not—which is unlikely.

One thought on “What Would Malcolm Forbes Say re Trump/Musk Space Policy?”