All images courtesy of Yulia A. Kraus

“Several factors seem to have contributed to create in Western society an ideological vacuum which imposes a single voice on many scientific and cultural issues.” —Swedish cytogeneticist Antonio Lima-de-Faria

The names of critical Russian evolutionary thinkers through the centuries fall “trippingly on the tongue”: Mendeleev, Oparin, von Baer, Lomonosov, Mechnikov, Gurwitch, Kozo-Polyansky, Berg, Beloussov, Cherdantsev, Dobzhansky, Schmalhausen, Skulachev, Pander, Stern, Koltzov, Koonin (now an American). . . But Western banking sanctions are currently preventing Russian scientists from participating in key international symposia and interfering in other ways with the dissemination of their work. The restrictions further canalize science. Esteemed Russian embryologist Yulia Kraus laments these developments, as she expressed in our recent interview.

Yulia Kraus leads EvoDevo research at both Lomonosov Moscow State University and Koltzov Institute of Developmental Biology of the Russian Academy of Sciences. Born in the Murmansk region—north of the Arctic Circle—she is the daughter of two medical doctors to whom she attributes her early passion for biology.

Kraus’s PhD in Embryology, Histology and Cell Biology is from Lomonosov Moscow State University, where she now teaches Evolutionary Developmental Biology in addition to leading the research there.

Prior to Western sanctions, Kraus had also been active on committees organizing meetings of the European Society for Evolutionary Developmental Biology and the International Society for Invertebrate Morphology.

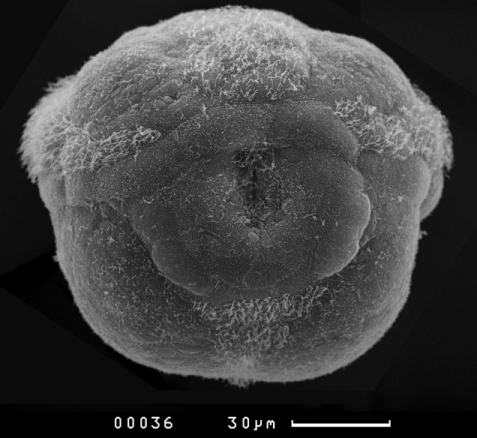

For roughly a quarter century, Kraus’s focus has been the morphogenesis of Cnidaria, the marine animal phylum first to appear with ectoderm/endoderm germ layers 600 million years ago. In her investigations, Kraus combines microsurgery with electron and confocal microscopy plus molecular biology. Her work follows in the morphogenetic, morphomechanical tradition of Lev Beloussov and Vladimir Cherdantsev—the latter her PhD advisor.

Kraus is cited for identifying the “organizer region” of Cnidaria associated with the blastopore, the first opening in the embryo.

Kraus’s papers have been featured in PNAS, Nature, International Journal of Developmental Biology, Development, Evolution and Development, among other journals. She also serves as co-Associate Editor of Ontogenez (Russian Journal of Developmental Biology).

I recently discussed Yulia Kraus’s research with Austrian biologist Uli Technau, one of her collaborators, who, in describing Yulia’s microsurgical and microscopy skills used the words: “magic hands.” (See images below.) Said Technau:

“Yes, I have collaborated with Yulia Kraus a couple of times. She is not only an excellent electron-microscopist, but she has magic hands and was able to show by blastopore lip transplantations of the sea anemone gastrula that it has the same axis-inducing properties as the dorsal blastopore lip of the amphibian embryo.”

My interview with Yulia Kraus follows.

Suzan Mazur: Do you come from a science family?

Yulia Kraus: My parents were both medical doctors. My mum worked in the functional diagnostics department, i.e., she made diagnoses based on electrocardiograms of various types and other similar methods. My dad was an anaesthetist and intensive care physician, one of the first in our region of Murmansk to specialize in intensive care. They loved their work and were always discussing physiological and biochemical bases of pathological conditions at home.

They also loved nature. As a family, we walked a lot in the forest and traveled frequently to the Black Sea. So, my parents were not surprised when I informed them that I wanted to become a biologist.

Suzan Mazur: How dynamic would you say Evolutionary Science research is at the moment in Russia?

Yulia Kraus: There are Evolutionary Biology laboratories and scientific teams in various areas of the country. Traditionally, these are centered in two cities: Moscow and St. Petersburg. However, there are several new promising laboratories—like at Kazan Federal University [in Kazan, capital of Tatarstan, Russian Federation].

My two professional positions, for example, are related to EvoDevo. I am lead researcher at the Department of Evolutionary Biology, Faculty of Biology, Lomonosov Moscow State University (MSU), and also group leader of the Morphogenesis Evolution lab at Koltzov Institute of Developmental Biology of the Russian Academy of Sciences (IDB RAS).

Other Russian teams are investigating EvoDevo at (1) the Department of Embryology, Faculty of Biology of St. Petersburg State University; (2) at the Institute of Gene Biology (Moscow); (3) at Shemyakin-Ovchinnikov Institute of Bioorganic Chemistry (Moscow); (4) as well as at Far Eastern National Scientific Center of Marine Biology (Vladivostok); and (5) A.N. Severtsov Institute of Ecology and Evolution (Moscow).

But I can’t say that we have enough world-class teams researching EvoDevo. The main problem is we lack potential group leaders ages 40 to 60. Many scientists had to leave the country in the 1990s and early 2000s.

[Note: Scientists emigrated from Russia in those years as the country restructured and financial crises ensued.]

At Koltzov Institute we’ve been updating our research equipment and offering good salaries to research scientists. However, it remains very difficult to find an embryologist both interested in the fundamental problems of EvoDevo and able to lead a research team.

Suzan Mazur: But, in recent decades you and other prominent Russian scientists, such as Lev Beloussov, Vladimir Cherdantsev and others, have importantly contributed to the investigation of form and spatial arrangement of embryonic cells. Lev Beloussov died several years ago, I understand. You published a paper with Vladimir Cherdantsev in 2003. Is he still a colleague of yours at Lomonosov Moscow State University?

Yulia Kraus: Sadly, Vladimir Cherdantsev died a few months ago, on 27 October 2023.

Suzan Mazur: I’m very sorry.

Yulia Kraus: Yes, he was an excellent embryologist and one of the first developmental biologists to understand the role of self-organization in early development. I was lucky because Vladimir Cherdantsev was my PhD supervisor.

Suzan Mazur: Why are Russian scientists not among the dozens of presenters at the upcoming “gastrula as organizer” centennial in Germany?

Yulia Kraus: This is mainly an organizational problem. I would be happy to take part in such a symposium, but, unfortunately, it is really difficult to do this. To go to a conference, it is not enough to submit an abstract and prepare a talk or poster. You need a visa. You have to pay an organization fee and purchase a ticket.

Russian scientists have money, but our cards don’t work outside Russia, and it’s impossible to transfer funds because foreign banks don’t accept payments.

It is very difficult or impossible to get a visa. I can apply, but I have very little chance of getting a visa. So, I prefer not to lose money and nerve cells attempting to participate in an international conference. Also, it’s important not to cause problems for colleagues who may want to invite me.

Suzan Mazur: It’s terrible to see science impacted in this way. Are you traveling at all?

Yulia Kraus: I travel a lot inside Russia, including trips to participate in scientific meetings. For example, I was very happy to visit Vladivostok in September 2023 to join the conference “Marine biology in the 21st century: developmental biology, molecular and cell biology, biotechnology of marine organisms”.

Suzan Mazur: Must be beautiful there with everything in blossom.

Yulia Kraus: Yes, there are many beautiful places in Russia. White Sea, where the MSU Biological Station is located, is one of the best ones.

Suzan Mazur: I visited Russia only once at Christmas time, in the late 90s. There was a dusting of snow in Moscow. Shops were bustling. I, of course, have the loveliest memories of the Bolshoi!

You are also co-Associate Editor of Ontogenez, the Russian Journal of Developmental Biology. The journal’s website notes:

“We welcome works on the mechanisms of embryonic and post-embryonic development in normal and pathological conditions, performed at the molecular, cellular, tissue and organism levels.”

Is Ontogenez open access and are international researchers welcome to submit articles? I do see that French, Austrian, German, US, UK, Japanese representatives as well as Russian are on the editorial board.

Yulia Kraus: Russian Journal of Developmental Biology has a hybrid publishing model. It is distributed by the Springer Nature Company. Yes, international scientists can publish open access papers in the journal, but payment to Springer is necessary and quite substantial.

Russian Journal of Developmental Biology is currently a Q4 [lower impact]. Of course, all international researchers are welcome to publish. We want to develop the journal as an open access state-of-the-art publication in developmental biology, focusing not only on model objects and systems but on non-conventional objects that can only be investigated through field studies.

Suzan Mazur: I recently highlighted some of your early research with Uli Technau on Cnidaria and the stunning Electron Microscopy you and your colleagues at Moscow State University produced. As you mentioned, you are currently group leader of the Morphogenesis Evolution lab at the IDB RAS as well as lead Evolutionary Biology researcher at MSU. Can you talk a little about your current science investigations?

Yulia Kraus: I have great colleagues at MSU and at IDB RAS. Right now we are researching different model organisms.

My colleague, Elena Voronezhskaya, invited me to collaborate in a study of embryonic development of the freshwater mollusk Lymnaea stagnalis. This mollusk is a classic model organism used in developmental biology, neurobiology, ecotoxicology, parasitology, biomineralization studies and even gerontology. It would seem that everything about its development is already known, but we were surprised to find no detailed description of the successive stages of Lymnaea embryogenesis.

Our study focuses on mesoderm and endoderm formation, axial organizer differentiation, and MAPK cascade dynamics. We also suggested a model of the slit-like blastopore formation and closure. Our results are a prerequisite for comparative analysis shedding light on how the shift to a freshwater environment impacts mollusk embryogenesis. We hope to publish the paper on Lymnaea embryogenesis shortly.

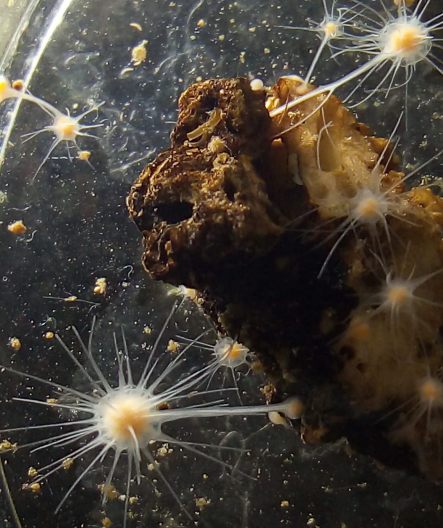

We are also beginning an investigation of carnivorous sponges, which are fantastic animals that lack a filter feeding system. Their morphology and feeding mode were described in 1995, by Nicole Boury-Esnault and Jean Vacelet (Aix-Marseille University, France).

Two weeks ago we won a grant from the Russian Science Foundation. We will look at coordinated cell behavior that leads to body plan formation in basal metazoans—the carnivorous sponge Lycopodina hypogea and the freshwater sponge Ephydatia fluviatilis. In the asexual reproduction of these animals, the juvenile sponge is formed by the assembly of individual cells during their coordinated migration. We hope to elucidate the role of self-organization in developmental processes based on the migration of individual cells.

The study of basal metazoans will provide unique information on the cellular and molecular basis of coordinated behaviour of individual cells. We will identify evolutionarily conserved elements of such coordination.

Suzan Mazur: I found your recent review of the highly diverse Cnidaria larvae breathtaking in scope. I saw a preprint of “Cnidarian larvae: true planulae, other-than-planulae, and planulae that don’t look like planulae“. Is the review now published?

Yulia Kraus: It has already been published in the Russian Journal of Developmental Biology, but I will keep the preprint on ResearchGate, thus ensuring open access to the paper.

Suzan Mazur: In the review you make the point that cnidarian pelagic larvae—pelagic from the Greek word for “open sea”. . . You make the point that early metazoan evolution should be studied in the context of life cycle, thus, your attention to cnidarian larvae, or planula as they are also known. One species you present already has the ability to hunt in the larval stage, which is fascinating.

Can you say a bit more about the review? It’s a wonderful paper. How long did it take to write?

Yulia Kraus: More than a year, but it was very interesting for me to find information on the different larval forms of cnidarians. I searched for the old papers, those published in the 19th century and first half of the 20th century. Normal development of various cnidarians was actively studied during those years, and then all studies were reduced mainly to a few model objects.

I was happy to find an article—rather a book—by John Graham Dalyell (1847) where the term “planula” was introduced. In the end, I realized that the diversity of cnidarian larvae is much greater than it seems at first glance.

When we use the term “planula” for all these larvae, we are hiding the diversity. It also became clear that the evolution of cnidarian larvae is linked to the evolution of their life cycles and reproductive strategies.

You are right, the predatory larva is fascinating. This is a larva of the sea anemone Aiptasia. The paper on this larva has been published in PNAS by the research team of Thomas Holstein (Maegele et al., 2023).

Yes, I point out in the paper that early metazoan evolution should be studied in the context of life cycle evolution.

The fact is that it is not the adult or larval phenotype that evolves, but the life cycle as a whole.

It is quite possible that a complex life cycle was the evolutionary starting point for metazoans, and that their ancestors were unicellular organisms with multicellularity as a facultative stage of a complex life cycle (see, for example, papers Ros-Rocher et al., 2021 and Sebé-Pedrós et al., 2017).

Suzan Mazur: In the review, you also say that a “highly conserved set of genes is involved in the patterning” of cnidarian and bilaterian larvae—what exactly do you mean? Swedish cytogeneticist Antonio Lima-de-Faria, who died several months ago at the age of 102, noted:

“The gene is only the bearer and the carrier, of the atomic order that already determined mineral symmetries. Moreover, due to the molecular mimicry an organism may not even need to have the same genes to produce the same structural pattern.”

Yulia Kraus: I meant that larvae of Bilateria and Cnidaria use the same (or similar) GRNs (genetic regulatory networks) to pattern the body plan. This is simply a fact. On the other hand, the same genes and GRN modules can be used to build completely different (non-homologous) structures. This is why it is very difficult to say with certainty that two structures are homologous (or not) based on molecular data.

Suzan Mazur: Some scientists would say that it’s really a systemic matter. University of Chicago microbiologist James Shapiro told me the following:

“I don’t use the word ‘gene’ because it’s misleading. There was a time when we were studying the rules of Mendelian heredity when it could be useful, but that time was almost a hundred years ago. The way I like to think of cells and genomes is that there are no ‘units.’ There are just systems all the way down.”

Yulia Kraus: It seems more correct to consider the developing organism as a whole system rather than breaking it down into isolated units. This applies not only to genes.

Some very interesting papers are now looking at development in terms of many factors at once, including the geometry and mechanics that coordinate the behavior of cells on the scale of the whole embryo. One such paper is “A mechanochemical model recapitulates distinct vertebrate gastrulation modes” (Serra et al., 2023). Historically, this approach can be traced back to the work of C.H. Waddington, I.I. Schmalhausen, L.V. Beloussov. It was this approach that laid the foundation for EvoDevo.

Suzan Mazur: Indeed, there are significant concerns about human genome editing for that reason, as reflected in US Food and Drug Administration Guidelines:

“Some of the specific risks associated with GE [genome editing] approaches include off-target editing, unintended consequences of on-target editing, and the unknown long-term effects of on- and off-target editing.”

Would you comment?

Yulia Kraus: Yes, this is a very serious risk, especially considering that each person’s genome is different and it is very difficult to predict all the consequences of any intervention. For each case we have to weigh the risks of the consequences of the disease and the editing. If editing is the only option, then I think it is reasonable to take the risk.

Suzan Mazur: Do you have time for outside interests such as art, sports, music?

Yulia Kraus: I do have time for outside interests, but not much. I like hiking—particularly in my home region of Murmansk—and nature photography. I enjoy cross-country skiing and roller-skating. Reading science fiction too. And I love to travel. . .

Great interview. Congratulations.

LikeLike