I first met Austrian biologist Ulrich (”Uli”) Technau at Paul Nurse’s star-studded 2008 Evolution conference at Rockefeller University—“From RNA to Humans: A Symposium on Evolution.” Technau’s presentation was on Cnidaria, the marine animal phylum first to appear with ectoderm/endoderm germ layers 600 million years ago, and an ongoing master of regeneration.

While some presenters at the two-day meeting seriously dressed down, as scientists often do at gatherings, Technau brought Viennese distinction to the event in an elegant European suit, as I recall.

Technau told me more recently that he had a pretty good fever at the time of the Rockefeller symposium but decided to keep his speaking commitment.

After the lectures, we spoke briefly at the cocktail party about his Cnidaria research at the University of Vienna where he was recently a full professor of developmental biology, following his PhD at the University of Frankfurt and studies at the Universities of Wurzburg, Mainz, Toulouse and LMU Munich.

I remember asking if he knew the Altenberg 16’s Gerd Müller, also a biology professor at University of Vienna. He advised that they worked in different areas of research.

Uli Technau has continued his focus on Cnidaria over the last two decades, investigating further the phylum’s ability to regenerate. His pivotal research on the two-germ layer Cnidaria, particularly the sea anemone, actually having “more than a hint” of a third layer (mesoderm) is discussed in our interview that follows.

Technau agreed to snatch 45 minutes from his schedule at the University of Vienna as Professor of Developmental Biology, Vice Head of the Department of Neurosciences and Developmental Biology, Vice Dean of Faculty of Life Sciences, Director/Ulrich Technau Lab, and as Science Ambassador to Austria’s High Schools to answer a few of my questions:

Suzan Mazur: We first met at Paul Nurse’s Evolution symposium at Rockefeller University in 2008—which now seems like the Stone Age of evolutionary science. You had recently published a paper on Cnidaria [the marine animal phylum includes sea anemones, hydras, corals, jellyfish, sea fans/pens & whips et al.] and presented some of your research to the standing-room-only crowd gathered there inside Buckminster Fuller geodesic dome. The significance of Cnidaria, as you explained, is that it is the first animal phylum to appear with germ layers [an obvious ectoderm and endoderm] and is a master of regeneration.

Where would you say the pulse is at the moment in evolutionary science? Mechanobiology? Neutron scattering and atomic biology? Human genome editing and in vitro gametogenesis?

Uli Technau: There are several lines of research where novel discoveries are being made, which have an impact on evolutionary biology. The long-standing questions on animal phylogeny have recently received completely new attention, through the use of gene syntenies as well as fusions and splits of chromosomal ancestral linkage groups as molecular synapomorphies instead of molecular phylogenies calculated from alignments of concatenated nuclear sequences. This has led to new views of early animal evolution.

Second, after the discovery of the importance of epigenetics—which in my view does not replace Darwinian evolution—mechanobiology has been (re-)discovered as a driving force in morphogenesis, although it is also clear that the underlying machinery is largely conserved, i.e., under positive selection.

[Note: Use of the term “selection” continues to be a problem. Who or what is the selector? See Lewontin, Ruse, Koonin, and Fodor.]

Third, single cell transcriptomics/genomics allows us to dissect and disentangle the evolution of morphological complexity of multicellular organisms.

Lastly, it has also become more and more clear, how the specific interactions with microbes have shaped the evolution of multicellular organisms, hence the idea of a holobiont or metaorganism.

Suzan Mazur: Has instrumentation overtaken personality-driven science?

Uli Technau: Yes and no. Advancements in technology have always driven science by opening new areas of research and levels of analyses. Think of the electron microscopy in the past, which has fueled several decades of ultrastructural research.

The recent development of cryo-EM is yet another deep dive into the molecular world on a nanoscale level. Also, the establishment of innovative bioinformatic tools such as AlphaFold to predict with high accuracy the structure of proteins as well as machine learning and AI methods to simulate complex dynamic processes are currently enhancing our possibilities enormously. For evolutionary biology, the establishment of single cell transcriptomics/genomics in combination with long-read sequencing methods to obtain chromosome-scale genome sequences has clearly democratized science in terms of the new blurred distinction between (genetic) model organisms and non-model organisms..

This is all tremendously important and insightful, although the high costs of these methods is still prohibitive for many labs. Nevertheless, despite these advances, conceptual ideas of individual thinkers remains essential as this allows hypotheses to be tested.

Suzan Mazur: Has the line between life and non-life become less significant in science?

Uli Technau: I don’t think so. This has always been a matter of debate and the answer largely depends on our definitions and criteria. However, how abiotic evolution allowed the transition to life remains one of the fascinating but also difficult areas of evolutionary biology.

Suzan Mazur: What is your lab currently investigating?

Uli Technau: I have a long-standing interest in the evolution of morphological complexity among animals, in particular the transition of diploblastic Cnidaria to the Bilateria. We have shown that the radial symmetry of many cnidarians (e.g., hydra and jellyfish) was likely secondarily lost, since sea anemones and corals display a second inner body axis and its establishment uses the same signaling pathway as bilaterians use to define the dorso-ventral body axis.

We challenged the view that the diploblastic cnidarians consist of only two germ layers—commonly associated with endoderm and ectoderm, lacking the mesoderm—but [we now know that] at least sea anemones have segregated domains of endodermal, mesodermal, and ectodermal germ layer identities.

Now we are investigating whether this segregation of three germ layers in a diploblastic topology is based on an ancestral, homologous gene regulatory network, as in other animals.

We are also addressing the question of the evolution of cellular diversification, in particular of muscles and neurons, using single cell transcriptomics in combination with transgenics. This will allow us to identify homologous but also convergently evolved cell types in cnidarians but also to dissect the physiological functions of these cells in the organism.

Suzan Mazur: You were recently in India. Was it a science-related visit?

Uli Technau: Yes, I was invited to a conference on development and regeneration at the Shiv Nadar University in Delhi. Great science and a fantastic organization. It was wonderful to meet so many Indian researchers from all levels doing excellent science.

Suzan Mazur: Regarding the September centennial symposium in Germany at the University of Freiburg celebrating Hilde Mangold’s and Hans Spemann’s discovery of the “gastrula as organizer”—where you’ll be a speaker,

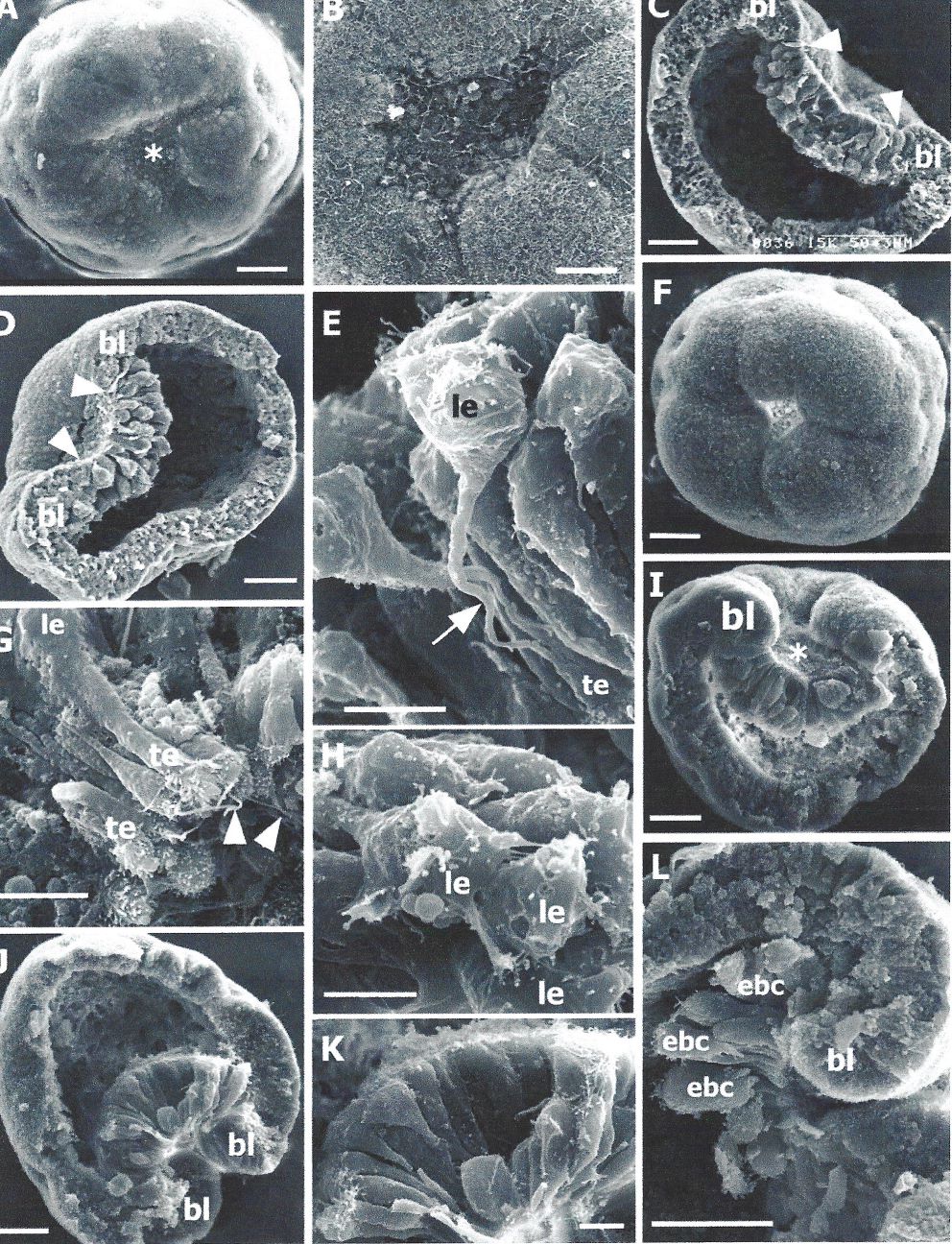

you published an ultrastructural study of sea anemone gastrulation almost 20 years ago with Russian scientist Yulia Kraus accompanied by stunning electron microscope images from Moscow State University.

A number of Russian scientists were investigating form and spatial arrangement of embryonic cells at that time. I’m thinking of Lev Beloussov, VG Cherdantsev, among others. However, not a single Russian scientist is on the list of some three dozen presenters at Freiburg. Why? Isn’t science supposed to be apolitical?

Uli Technau: Yes, I have collaborated with Yulia Kraus a couple of times. She is not only an excellent electron-microscopist, but she also has magic hands and was able to show by blastopore lip transplantations of the sea anemone gastrula that it has the same axis-inducing properties as the dorsal blastopore lip of the amphibian embryo.

Russian scientists have made important contributions in the past, e.g., with the phenomenon of mechanotransduction at a time when biology was dominated by genetics. But in the last decade, it seems the conditions to be competitive in science have become very difficult in Russia. The war against Ukraine has not made this easier.

Suzan Mazur: What is the subject of your upcoming Freiburg presentation?

Uli Technau: I will present some new fascinating data on the self-organizing capacities of dissociated and reaggregated gastrula cells, including the role of the blastopore lip cells on axis formation and re-establishment of germ layers. This connects to my own PhD work, where I studied self-organization of an organizer in hydra aggregates.

Suzan Mazur: Regarding a biological organizer—physical chemist Bogdan Dragnea told me the following during our 2018 book interview:

“[A]t the scale of biological organelles below 100 nanometers many phenomena have characteristic energies that converge there. . . .Thermal energy. Mechanical energy. And chemical energy. Especially those bonds that are prevalent within the molecules of life. They all converge in magnitude at that special scale. There is cross-talk.

This means you have the link between mechanics and thermodynamics and the link between thermodynamics and quantum mechanics and they all mix there in the region between 10 nanometers and 100 nanometers. It’s that area, in particular, of mechanobiology that’s going to be extremely interesting and challenging because of the mixing of these scales.”

Uli Technau: I cannot comment much on this. Some people say that we have to explain everything by quantum mechanics. I do believe different scales have emergent properties that cannot be explained easily by the knowledge of the components of the smaller scale.

Suzan Mazur: In addition to your research, teaching, and administrative work at the University of Vienna, you are Science Ambassador to Austria’s High Schools. Can you talk about that? Was your interest in biology sparked during your own high school years?

Uli Technau: I would probably not be here researching and teaching if I had not had a biology teacher in high school who inspired me. To give some of that back, I am regularly visiting high schools to convey my life-long enthusiasm and fascination of life.

What students often want to know is how I became a scientist. What my daily life looks like. And why I am not getting bored investigating cnidarians after so many years!

The second reason I chose this ambassadorial role is to fight the growing skepticism of science by explaining to students how scientists work and why being wrong as an individual researcher is nothing bad. It does not make all of science false.

Great interview!

LikeLike